Strange Stranglets?

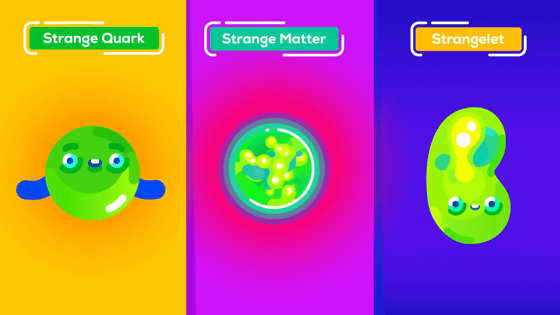

As previously mentioned, neutrons consists of two down quarks and an up quark. But under particularly extreme pressures and densities, when all lower energy levels are filled, a new possibility arises. Some energy can be expended to turn down quarks into more massive "strange" quarks. The introduction of these strange quarks allows for new configurations, unlocking a new set of energy levels. By accessing these new, lower, energy levels, the energy required to transmute down quarks can be recouped. Thus, the average energy of the particles decreases. Matter that contains strange quarks is referred to as strange matter.

Strange matter is generally though to form blobs, referred to as strangelets, which can range in size from the scale of nuclei to arbitrarily large. When they get to the size of meters, stranglets are usually referred to as strange stars. Quantum chromodynamics, or QCD, predicts that strange matter is unstable on the tiniest of scales (individual particles), because of the increased mass of the strange quark. However, it also predicts that on larger scales, precisely because of the aforementioned lower energy levels that the presence of strange quarks allows for, strange matter may become more and more stable the more of it there is.

There's another aspect to strange matter, that is considerably more sinister in nature. According to the Bodmer-Terazawa-Witten hypothesis, strange matter, even outside of a neutron star, is more stable than ordinary matter. But to understand what this means, we need to understand what "stability" even means.

"Stability" is a measure of something's reluctance to change. A pen balanced on its tip is very unstable, and changes readily. A stone on the ground, by contrast, is relatively stable, and does not begin rolling over of its own accord. Crucially, however, stability is relative; there is no absolute stability, merely "more stable" and "less stable".

So when we say that strange matter is more stable than ordinary matter, what do we actually mean? We mean that, just like a pen balanced on its tip "wants" to fall down, ordinary matter "wants" to turn into strange matter. We mean that, past a certain point, the transition of ordinary matter into strange matter should be automatic, and indeed, unstoppable.

If we follow this line of reasoning, all ordinary matter should slowly decay into strange matter, with each medium-size strangelet produced resulting in an ever-expanding strange star consuming everything in its vicinity, releasing tremendous amounts of energy in the process. However, for a nucleus to form a stable stranglet, many down quarks would have to near-simultaneously transmute into strange quarks, so even if this hypothesis is true, we likely do not have to worry about cosmic armageddon. Still, the possibility of strange matter is something that scientists are still actively looking into.

References

- E. Witten, "Cosmic separation of phases", Phys. Rev. D., vol. 30 272, 15 July 1984, doi: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.30.272

- A. Charles, F. Edward, O. Angela, "Strange Stars", Astrophysical Journal, vol. 310 p.261-272, November 1986, doi: 10.1086/164679

- T. Klähn, D. Blaschke, "Strange Matter in Compact Stars", EPJ Web Conf., vol. 171, 08001, February 2018

Images

Kurzgesagt - In a Nutshell "The Most Dangerous Stuff in the Universe - Strange Stars Explained"